Criminal Law in India: New Legal Framework

Dated

0

Comments

Criminal Law in India: New Legal Framework

Criminal law represents one of the most consequential areas of legal practice, addressing conduct deemed harmful to society and prescribing punishments ranging from imprisonment to fines. For Indian legal professionals, 2024 marked a transformative moment in the criminal justice system: the comprehensive modernization of 162-year-old British-era legislation. Effective July 1, 2024, three foundational enactments—the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita 2023 (substantive criminal law), the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita 2023 (procedural law), and the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam 2023 (evidence law)—replaced the Indian Penal Code (1860), Criminal Procedure Code (1898), and Indian Evidence Act (1872) respectively, fundamentally reshaping criminal practice. This comprehensive reform reflects India's commitment to aligning its criminal justice system with contemporary societal values, technological advancement, and international best practices.

Understanding Criminal Law: Scope and Modern Developments

Criminal law differs fundamentally from civil law in its purpose, burden of proof, and available remedies. While civil law addresses disputes between private parties with compensation as the primary remedy, criminal law prosecutes individuals on behalf of the state for conduct harmful to public order and social stability, with punishment (imprisonment, fines) as the primary remedy and "beyond reasonable doubt" as the evidentiary standard. The distinction carries profound consequences: a criminal conviction carries social stigma and liberty implications that civil liability does not.

The transition to India's new criminal law framework represents far more than legislative renumbering. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita introduces substantive crimes addressing modern criminal conduct (cybercrime, environmental violations, mob lynching) that the 1860 IPC inadequately addressed. The procedural reforms in the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita mandate digitalization of processes, videography in searches and seizures, and integration of forensic science to enhance transparency, accountability, and investigative quality. The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam modernizes evidence rules to accommodate digital and electronic records—a critical evolution given the centrality of digital evidence in contemporary criminal cases.

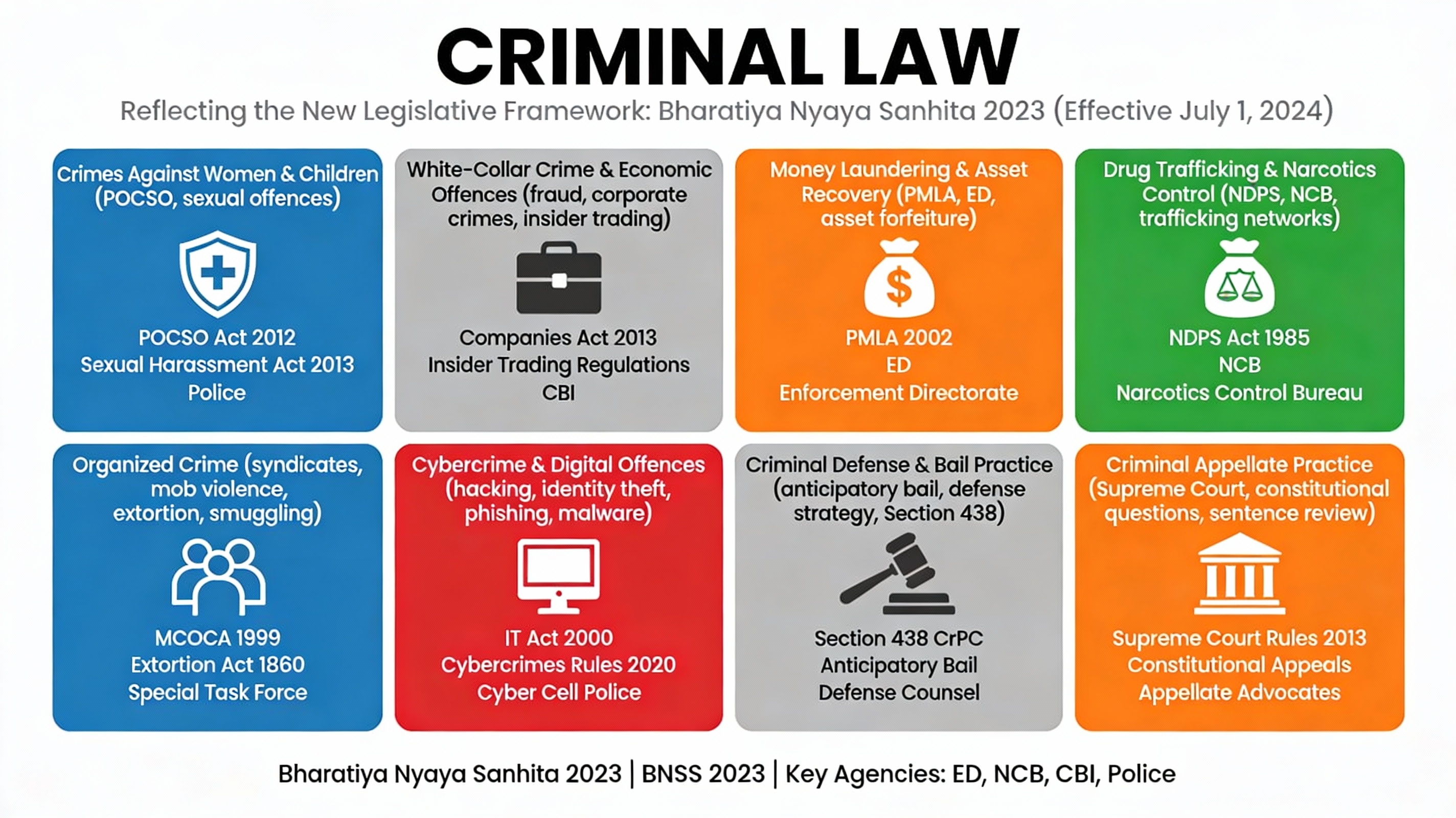

Criminal Law in India - Comprehensive Framework Infographic

Core Practice Areas in Criminal Law

1. Crimes Against Women and Children: Specialized Protection Framework

Crimes against women and children represent one of the highest-priority practice areas within criminal law, reflecting both societal emphasis on protecting vulnerable populations and judicial commitment to expeditious justice delivery.Sexual Offences Under the New Framework

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita significantly strengthened protections against sexual crimes, introducing stringent penalties reflecting heightened societal concern with sexual violence. The framework distinguishes among multiple offence categories based on the nature of the assault and victim's age.

Penetrative Sexual Assault carries imprisonment of 10 years to life (for victims 16 years and older) or 20 years to life imprisonment (for victims under 16), with mandatory fines. Aggravated Penetrative Sexual Assault—involving multiple assailants, use of weapons, or extreme brutality—triggers more severe punishment: 20 years to life imprisonment or even the death penalty. These enhanced penalties, particularly for crimes involving minors, reflect legislative recognition that sexual violence against children constitutes one of society's most heinous acts.

POCSO Act 2012: Specialised Framework for Child Protection

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act 2012 provides a comprehensive, child-centric framework addressing sexual exploitation of minors. The Act establishes multiple offence categories with graduated penalties. Penetrative Sexual Assault (Section 3-4) involves insertion of the penis, objects, or manipulation causing penetration, carrying 10 years to life imprisonment and mandatory fines. Aggravated Penetrative Sexual Assault (Section 5-6)—involving multiple assailants or abuse of authority—carries a minimum 20 years imprisonment, potentially extending to the remainder of natural life, with the optional death penalty.

Sexual Assault (Section 7-8) addresses non-penetrative sexual contact—touching vagina, penis, anus, or breasts with sexual intent—carrying 3-5 years imprisonment and fines. Aggravated Sexual Assault (Section 9-10) covers similar conduct by persons in positions of authority or involving use of intoxicants, carrying 5-7 years imprisonment. Sexual Harassment (Section 11-12) addresses verbal or non-contact sexual conduct, punishable by imprisonment up to 3 years and fines.

Critical to POCSO practice is understanding the Act's sophisticated approach to child-friendly investigation and trial. The statute mandates the protection of child privacy, the prohibition of the identification of victims, in-camera proceedings, and trained officers conducting interviews. These mechanisms recognise that sexual abuse of children requires specialised procedural protections beyond standard criminal adjudication.

Concurrent Criminal Liability

An important practical issue emerges when sexual offences against children violate POCSO provisions simultaneously with IPC/Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita provisions. A landmark Delhi High Court decision (Kanha v. State of Maharashtra) held that an accused convicted under Section 376(2)(f)(i) of the IPC (aggravated rape of a minor under 12 years) can simultaneously be convicted under POCSO's Section 4 (Penetrative Sexual Assault of a victim under 12). The court applies the principle that one penal statute does not exclude another—the accused faces trial and conviction under both statutes. However, importantly, Section 71 of the IPC (now incorporated in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita) prevents double punishment: the court imposes the graver sentence available under either statute but does not cumulate sentences.

Violence Against Women Framework

Beyond sexual offences, the new criminal law framework addresses gender-based violence comprehensively. Stalking, acid attacks, dowry-related harassment, and other forms of gender violence receive explicit statutory attention with stringent penalties designed to deter and proportionately punish such conduct. The reduction in trial timelines for crimes against women reflects judicial recognition that swift justice serves victims' interests and deters perpetrators.2. White-Collar Crime and Economic Offences: Sophisticated Financial Criminality

White-collar crime—offences committed by individuals in positions of trust involving financial gain through deception—represents one of the fastest-growing criminal domains as India's economic sophistication expands. These crimes, perpetrated by corporate executives, financial professionals, and government officials, often cause greater aggregate economic harm than street crimes but receive less public attention.

Corporate Fraud and Financial Misrepresentation

The IL&FS financial crisis of 2018 exemplified how corporate fraud can systematically deceive regulators and investors. IL&FS artificially inflated its financial position, triggering liquidity crises affecting banking, infrastructure, and capital markets sectors. The case revealed systemic failures in corporate governance oversight, internal control, and regulatory monitoring—failures that criminal prosecution attempted to remedy post facto.

Modern corporate fraud takes numerous forms: Ponzi schemes involving false promised returns on investments, insider trading involving trading on material non-public information, and large-scale financial scams involving complex financial instruments. Each variant requires specialized forensic knowledge, financial statement analysis, market operation understanding, and regulatory framework mastery.

Cyber-Enabled White-Collar Crime

The intersection of technology and financial crime has created new criminal vectors. The 2018 cyberattack on Cosmos Bank exposed critical vulnerabilities: cybercriminals deployed malware and computer command manipulation to siphon ₹94 crores, revealing systemic banking cybersecurity inadequacies. The case demonstrates that white-collar crime's modern iteration increasingly leverages digital systems and exploits cybersecurity vulnerabilities, requiring practitioners to develop a sophisticated understanding of both financial crime methodologies and cyber forensic investigation.

Corporate Espionage and Insider Information Misuse

The National Stock Exchange (NSE) co-location scandal exemplified sophisticated insider information misuse. Brokers allegedly obtained preferential access to NSE's trading platform, enabling execution of trades before competitors and leveraging proprietary market information. Such cases reveal how competitive pressures in IT, pharmaceuticals, energy, and financial services create incentives for theft of sensitive information—practices that harm market integrity and fair competition.

Regulatory Crackdown and Enforcement Evolution

Recognising white-collar crime's economic significance, Indian regulators substantially intensified enforcement. The Prevention of Money Laundering Act has facilitated tracking of financial fraud proceeds, leading to deregistration of over 300,000 shell companies used to launder illicit funds. The Fugitive Economic Offenders Act enabled asset confiscation from absconding high-profile offenders like Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi, recovering wealth generated through fraud. These enforcement measures signal the government's commitment to holding economically powerful offenders accountable despite their sophisticated defence capabilities.

3. Money Laundering and Asset Recovery: Financial Crime Investigation

Money laundering—the process through which illicit funds generated from predicate crimes are disguised as legitimate earnings—represents a critical practice area at the intersection of criminal law, financial regulation, and international cooperation.

PMLA Framework: Prevention of Money Laundering Act 2002

The Prevention of Money Laundering Act 2002, administered by the Enforcement Directorate (ED), provides India's primary statutory mechanism for prosecuting money laundering and recovering proceeds of crime. The framework operates on a critical principle: money laundering constitutes an independent offence distinct from the predicate crime (drug trafficking, terrorism, corruption) generating the illicit funds.

Section 3 of PMLA establishes the money laundering offence: Whoever knowingly processes proceeds of crime with the objective of projecting unlawful money as lawfully earned wealth, or acquires, possesses, uses, or transfers proceeds of crime, commits the money laundering offence. Conviction carries life imprisonment (up to 7 years) and substantial fines, with no fine cap specified in certain circumstances.

The statute's critical innovation lies in Section 24, which reverses the burden of proof. Once the prosecution establishes sufficient material linking the accused to proceeds of crime, the accused must affirmatively prove the money's legitimacy. This burden-shifting deviates from the "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard applicable to other criminal offences and has withstood constitutional challenges. The Supreme Court in Vijay Madanlal Choudhary v. Union of India upheld PMLA's constitutionality, reasoning that money laundering's serious economic offence character justifies stricter proof requirements.

Predicate Offences and PMLA Applicability

A critical issue in PMLA practice involves determining whether a predicate offence triggering PMLA applicability occurred. PMLA applies only when proceeds trace to a "scheduled offence"—categories defined in PMLA regulations, including terrorism, drug trafficking, corruption, financial fraud, and human trafficking. The Supreme Court has held that scheduled offences are essential prerequisites: PMLA does not apply to proceeds of unscheduled crimes, even if serious. This jurisdictional requirement creates important defences for accused persons charged with money laundering based on proceeds allegedly from non-scheduled crimes.

ED's Quasi-Judicial Powers

Section 50 of PMLA grants the ED quasi-judicial powers to summon witnesses and record statements during investigations. The statute provides that statements recorded by ED are voluntary and admissible in court proceedings, though courts have held that physical torture or coercion renders statements inadmissible under constitutionally protected rights. The ED possesses the authority to impose fines for non-compliance with summonses, with penalties capped at ₹500 per violation. These broad investigative authorities represent enforcement muscle designed to trace and recover illicit assets but require careful oversight to prevent abuse.

Continuing Offence Doctrine and Continuing Liability

An important PMLA principle holds that money laundering constitutes a "continuing offence"—liability extends beyond conviction or acquittal of the scheduled predicate offence. Even if the predicate crime (drug trafficking, terrorism) is acquitted, PMLA charges may proceed if evidence establishes that the accused laundered proceeds from that acquitted crime or other qualifying offences. This doctrine creates unusual scenarios where PMLA convictions may occur despite acquittal of underlying crimes, reflecting legislative recognition that money laundering perpetuates crime's economic harms even after underlying criminal conduct concludes.

Asset Forfeiture and Economic Rehabilitation

Once money laundering is established, civil asset forfeiture mechanisms enable state seizure and confiscation of proceeds without requiring criminal conviction. The ED possesses power to freeze bank accounts, seize property, and initiate provisional attachment before trial concludes, depriving accused persons of illicit assets during the investigation. While procedural safeguards exist—requirements for reasonable belief that assets constitute proceeds of crime and notice to affected parties—these mechanisms concentrate significant power in executive investigative agencies with limited judicial oversight.

4. Drug Trafficking and Narcotics Control: Multi-Agency Enforcement

Drug trafficking represents one of India's most serious organised crime challenges, generating estimated billions in illicit revenue and fueling addiction, violence, and collateral crime. The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act 1985 provides the statutory framework for narcotics law enforcement, with implementation across federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

NDPS Classification and Controlled Substances

The NDPS Act's preventive architecture rests on scheduling controlled substances into three categories. India has scheduled 134 narcotic drugs (heroin, opium, cocaine, cannabis), 173 psychotropic substances (MDMA, amphetamines, benzodiazepines), and 45 controlled substances (precursors and chemicals used in drug manufacture). This scheduling system enables regulatory control of both finished illicit drugs and precursor chemicals essential for manufacture, creating comprehensive supply chain barriers.Multi-Tier Enforcement Architecture

Drug law enforcement involves unprecedented federal-state-local coordination through a sophisticated 4-tier Narco-Coordination Centre (NCORD) mechanism established by the government. The National Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) operates as the principal federal agency, recently expanded with 536 new positions across multiple levels. The NCB's organisational restructuring increased regional offices from 3 to 7 and upgraded sub-zones to create 30 zonal units across India, with special focus on cyber, legal, and enforcement components for enhanced effectiveness.Each state and union territory operates an Anti-Narcotics Task Force (ANTF) headed by an Additional Director General or Inspector General-level officer, functioning as the NCORD secretariat and ensuring compliance with the federal drug law enforcement strategy. This hierarchical coordination mechanism ensures that federal priorities are implemented through state capacity while maintaining consistent enforcement standards.

Expanded Law Enforcement Authority

Recent reforms substantially expanded enforcement authority across multiple agencies. Border Guarding Forces (Border Security Force, Assam Rifles, Sashastra Seema Bal) received explicit NDPS Act empowerment to conduct searches, seizures, and arrests at international borders for drug trafficking. The Railway Protection Force similarly gained authority to check drug trafficking along rail routes, recognising that drug smugglers frequently exploit railway transportation networks.

Coordination has deepened across federal and state agencies. The Joint Coordination Committee, chaired by the NCB Director General, monitors important and significant drug seizures, ensuring investigative quality and facilitating intelligence sharing. Joint operations involving Navy, Coast Guard, Border Security Force, and state ANTF agencies conduct coordinated enforcement against international smuggling networks.

Practical Enforcement Statistics

Data reflects enforcement intensity: In 2024, drug law enforcement agencies registered 89,913 cases, made 116,098 arrests, and seized 1,330,600 kilograms of drugs. These statistics reflect enforcement efforts against multiple drug types—heroin, cocaine, ganja (cannabis), MDMA/Ecstasy, opium, and pharmaceutical controlled substances (cough syrups containing codeine, benzodiazepines)—across urban and rural India.5. Cybercrime and Digital Offences: Technology-Enabled Criminal Conduct

Cybercrime represents the fastest-growing criminal domain in India, reflecting the exponential expansion of digital transactions, internet usage, and cloud-based operations that create novel criminal vulnerabilities. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita explicitly addresses cybercrime, recognising that traditional legal categories inadequately address technology-enabled conduct.

Cybercrime Typologies

Cybercrimes encompass multiple distinct offences: Hacking (unauthorized computer access), Identity Theft (stealing personal or financial credentials), Online Harassment and Cyberbullying (threatening or defamatory digital communications), Phishing (false emails/websites inducing credential disclosure), Fraud (financial deception through digital means), Data Breaches (unauthorized disclosure of protected information), Malware Distribution (deployment of harmful software), and Distributed Denial of Service attacks (DDoS—overwhelming systems with traffic to disable services).

Each cybercrime variant requires specialised investigative expertise. Hacking investigations demand forensic IT specialists who can trace unauthorized system access, recover deleted files, and identify attacker methods. Fraud investigations require financial forensics and transaction tracing. Phishing cases demand understanding of email authentication and DNS spoofing. The lack of sufficient cyber-forensic expertise in investigating agencies creates persistent challenges in cybercrime investigation quality.

Concurrent Liability: IT Act and IPC Charges

A critical practical issue in cybercrime prosecution involves prosecuting offences simultaneously under the Information Technology Act 2000 and the Indian Penal Code (now Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita). A cybercriminal who sends threatening emails might violate both Section 66 of the IT Act (hacking/unauthorised access) and Section 499-505 of the IPC/BNS (defamation/criminal intimidation).The principle of concurrent liability permits prosecution and conviction under both statutes; both the FIR (First Information Report) and chargesheet must include charges under both enactments if evidence supports both. However, critically, Section 71 of the IPC (incorporated in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita) prevents double punishment: the court must impose the graver sentence available under either statute but cannot cumulate sentences. This approach protects against arbitrary punishment escalation while enabling comprehensive legal accountability.

Digital Evidence and Procedural Evolution

The Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam 2023 substantially modernises evidence law to accommodate digital evidence. The new framework explicitly addresses: Admissibility of electronically stored data, Digital signature authentication, Email and message evidence, Cloud-stored records, and even Artificial Intelligence-generated content. These provisions recognise that contemporary criminal cases depend overwhelmingly on digital evidence—communications, financial transactions, location data, surveillance footage—requiring evidentiary frameworks expressly designed for technological reality.The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita mandates videography in searches and seizures, creating permanent audio-visual records that constrain police misconduct and preserve evidence authenticity. This procedural reform reflects international best practices and responds to decades of judicial concern with false "discoveries" during raids and searches.

6. Organized Crime: Criminal Syndicates and Structured Violence

Organized crime—criminal activity conducted by hierarchical criminal enterprises operating across jurisdictions—represents one of India's most intractable challenges, generating billions in illicit revenue through drug trafficking, human trafficking, extortion, contract violence, and smuggling.

Syndicate Structures and Criminal Networks

Modern organized crime operates through specialized criminal syndicates with division of labor, defined territories, operational protocols, and corruption of government officials. Drug trafficking syndicates integrate cultivation, manufacture, trafficking, distribution, and money laundering into vertically integrated enterprises. Human trafficking networks operate along established routes with infrastructure for victim transportation, exploitation, and exploitation-revenue capture.

Statutory Framework for Organized Crime

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita 2023 introduces explicit "Organized Crime" offences addressing structured criminal enterprises (and distinct "Petty Organized Crime" for less sophisticated operations). Additionally, multiple specialized statutes target specific organized crime manifestations: The NDPS Act addresses drug trafficking networks, the Prevention of Money Laundering Act disrupts financial infrastructure enabling organized crime, the Immoral Traffic Prevention Act addresses human trafficking, and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act addresses terrorism-related organized crime.

Mob Lynching: New Statutory Emphasis

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita introduces mob lynching as a distinct statutory offense, reflecting heightened societal concern with vigilante violence where crowds summarily execute perceived offenders without judicial process. Mob lynching provisions address the specific dynamics of crowd-enabled violence and the individual culpability questions arising when multiple actors collectively commit violence.7. Criminal Defense Practice: Bail, Anticipatory Bail, and Defense Strategy

Criminal defense practice addresses representation of individuals accused of crimes, advocating for constitutional rights protection, scrutinizing prosecution evidence, and developing strategic defenses to secure acquittal or sentence reduction.

Bail Jurisprudence: Constitutional Right to Reasonable Bail

Bail—conditional release pending trial or appeal—represents one of criminal law's most consequential doctrines. The Supreme Court has established that bail constitutes a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution, recognizing that pre-trial detention presumes guilt in violation of the innocent-until-proven-guilty principle. However, courts possess discretion to deny bail when the accused poses flight risk (likelihood of absconding to avoid trial) or danger risk (likelihood of committing further crimes or tampering with evidence/witnesses).

Anticipatory Bail: Pre-Arrest Protection Mechanism

Section 438 of the Criminal Procedure Code (now equivalent provisions in Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita) provides anticipatory bail—relief granted in anticipation of arrest before actual arrest occurs. An individual facing investigation or probable arrest for non-bailable offences can apply to the sessions courts or high courts for advance bail orders that protect against arrest upon specific conditions.

The scope of anticipatory bail is potentially broad, but courts exercise discretion carefully, applying factors including: Nature and gravity of the offence (serious offences like murder or rape disfavour bail), Likelihood of misuse (whether bail conditions will be violated or evidence tampered), Past conduct and criminal history, and Cooperation with investigation. Courts frequently impose conditions: Mandatory appearance for interrogation whenever required, Restrictions on travel/international departure without permission, Non-interference with witnesses or evidence, and Execution of bonds with or without sureties.

The Supreme Court established in landmark bail jurisprudence that anticipatory bail is discretionary, not a matter of right; it should not be granted as a matter of course but only when a genuine apprehension of false or baseless charges exists. This doctrine prevents the routine grant of pre-arrest bail but acknowledges that some individuals genuinely face unfounded prosecution risks.

Defence Strategy: Evidence Scrutiny and Witness Credibility

Criminal defence practice demands rigorous scrutiny of the prosecution's case. Defenses typically challenge: Evidence authenticity and proper collection procedures (unlawful searches violate constitutional protections and make evidence inadmissible), Witness credibility and consistency (contradictions between testimony and prior statements undermine reliability), Investigation quality (shortcuts, bias, or negligence call findings into question), and Circumstantial evidence sufficiency (requires complete chain linking accused to crime, not inference gaps).

The burden of proof standard—prosecution must prove guilt "beyond a reasonable doubt," a high threshold requiring moral certainty—creates significant defence leverage. Even strong circumstantial evidence may be insufficient if reasonable alternative explanations exist.

Custodial Torture and Rights Protection

Criminal defence practice necessarily involves addressing police misconduct—custodial torture, forced confessions, fabricated evidence. Indian courts have increasingly recognised custodial torture as violating fundamental rights and rendering confessions involuntary and inadmissible. High courts possess jurisdiction to grant remedies, including damages, criminal prosecution of officers, and case quashing when rights violations occur.

8. Criminal Appellate Practice: Appellate Standards and Sentence Review

Criminal appeals address convictions or sentences imposed by trial courts, with appellate courts exercising appellate review to correct legal errors, examine evidentiary sufficiency, and assess sentence proportionality.

Supreme Court Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction

Article 134 of the Constitution establishes Supreme Court jurisdiction over criminal matters limited to three scenarios: (1) Death sentences imposed or upheld by high courts (automatic appellate jurisdiction); (2) Cases where high courts certify fitness for Supreme Court appeal (discretionary jurisdiction); and (3) Constitutional or questions of substantial legal importance. This jurisdictional framework, more restrictive than civil appellate jurisdiction, reflects criminal law's finality emphasis and federalism principles, reserving most appellate matters to high courts.

Appellate Review Standards

Appellate courts apply distinct standards when reviewing trial court decisions. Pure questions of law are reviewed de novo (afresh, without deference to the trial court). Factual findings receive substantial deference unless clearly unreasonable, perverse, or unsupported by evidence. Sentence appropriateness is reviewed against proportionality standards—ensuring punishment fits crime severity and offender culpability rather than the trial judge's personal preferences.

High Court Appellate Jurisdiction

State high courts maintain extensive appellate jurisdiction over trial court convictions, acquittals, and sentence determinations. High courts review felony convictions, assess whether evidence was sufficient to sustain convictions "beyond reasonable doubt," and evaluate whether sentences are proportionate and compliant with statutory guidelines. Additionally, high courts exercise criminal revision jurisdiction, allowing review of lower court procedural orders and bail decisions on grounds of legal error or procedural impropriety.

Practical Considerations in Modern Criminal Practice

Procedural Modernization Under New Laws

The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita's implementation has introduced significant procedural changes requiring practitioners to master new mechanisms. Online FIR registration, digital evidence management systems, and mandatory videography of searches and seizures represent operational changes affecting investigation quality and evidence admissibility. Practitioners unfamiliar with new procedures risk losing critical evidentiary advantages or procedural defenses available under the reformed framework.

Mental Health and Forensic Psychology Integration

Contemporary criminal practice increasingly incorporates mental health considerations. The insanity defense (not criminally responsible due to mental illness), diminished capacity defenses, and mental health sentencing mitigation require forensic psychiatric expertise. Courts increasingly appoint mental health experts to assess criminal responsibility, competency to stand trial, and appropriate mental health sentencing considerations.

Coordination with Specialized Agencies

Criminal practice increasingly requires coordination with specialized investigative agencies: ED (money laundering), NCB (drug trafficking), CBI (federal crimes), and cyber forensics labs. Understanding these agencies' operating procedures, evidence standards, and jurisdictional limitations is essential for effective advocacy.

Conclusion: Criminal Law as Gateway to Justice System Mastery

Criminal law practice requires mastery of substantive crime definitions, procedural regulations, constitutional protections, and strategic advocacy skills. The July 2024 implementation of India's reformed criminal laws presents significant opportunities for practitioners willing to invest in understanding new frameworks, modernized procedures, and technology-integrated investigation and evidence standards. The practice areas span from protecting society's most vulnerable members (children, women) through sexual offence prosecution, to constraining organized crime through sophisticated asset recovery mechanisms, to defending individuals' constitutional rights against state power.

The most accomplished criminal practitioners combine technical statutory expertise with constitutional knowledge, investigative understanding, and courtroom advocacy skills. As India's criminal justice system continues evolving toward technology integration, victim protection, and efficiency, lawyers mastering these domains will serve critical roles in ensuring both public safety and individual rights protection—the fundamental tensions that criminal law perpetually negotiates.

Tags :

Criminal Law

Post a Comment